This article is part one of a two-part series on private school vouchers in Washington, D.C. For part two, click here.

When Congress created the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program nearly 20 years ago as the country's first and only federally funded private school voucher program, supporters envisioned the program as a model for expanding school choice nationally.

If the slow speed of federal bureaucracy could make this happen in Washington, D.C., it could be done anywhere, proponents said at the time.

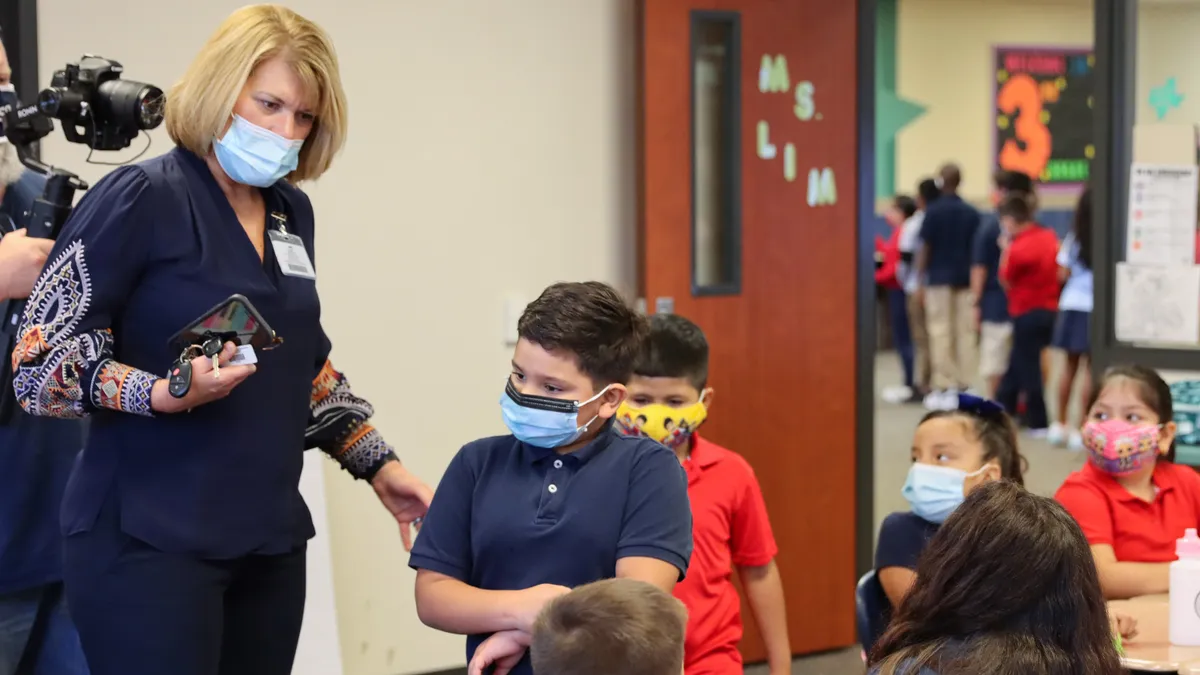

The program, which has continuously run since 2004, provides low-income students in the nation's capital with tuition to attend secular or religious private schools within the progressive city's borders. Over the past 20 years, about 11,800 elementary and secondary students have participated in the D.C. program.

Back when it was created, only a handful of state-funded school voucher programs existed elsewhere.

"I would argue that D.C. relaunched, in many ways, this sort of parent phase [of empowerment] and the voucher movement across the country," said Robert Enlow, president and CEO of EdChoice, a pro-school-choice organization.

The private school voucher movement in the U.S. has exploded in recent years. Today's landscape includes 25 voucher programs in 14 states, D.C. and Puerto Rico serving 312,443 students, according to EdChoice. Just this year alone, six states expanded or created school choice programs that use taxpayer dollars, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has reported.

And despite private school vouchers being one of the most highly legislated, litigated, researched and debated issues in education, supporters predict the momentum for these and other school choice programs will only continue to grow — fueled by parent demand brought on by pandemic-related learning setbacks and other frustrations with public schools.

In D.C., where public and private school choice is already abundant and where public school students can enter a lottery to attend public schools outside of their own school boundaries, there's fierce competition for students. Leaders and supporters of the three publicly funded schooling options — traditional public schools, public charter schools and the voucher program — all say they need bigger budgets so they can do more for their students.

I would argue that D.C. relaunched, in many ways, this sort of parent phase [of empowerment] and the voucher movement across the country.

Robert Enlow

President and CEO of EdChoice

Enlow and others call the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program a "lifeline" that has helped thousands of poor students in the nation's capital escape underperforming public schools and has empowered their parents.

That's not, however, how opponents see it.

Those pushing for the program’s demise say it has been ineffective for participating students and unaccountable to taxpayers. The voucher program, they say, drains money from traditional public schools and ignores federal nondiscrimination policies, such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act for students with disabilities.

In general, participating private schools are prohibited from discriminating against program participants or applicants on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion or gender. But some caveats apply to single-sex and religious private schools. Opponents say there's little publicly reported oversight of nondiscrimination compliance at the participating schools.

"I will sometimes get sort of all worked up thinking about one school on one corner and another on the other, and they are equally funded by the government, because one is a public school and one has 85-90-100% voucher money with completely different rules," said Maggie Garrett, vice president of public policy for Americans United for Separation of Church and State.

D.C.'s voucher program "just seems like complete fiction to me," said Garrett, who co-chairs the National Coalition for Public Education, a group that opposes using public money for tuition at private schools.

Public school advocates also point out that nationwide 9 out of 10 students attend a public school, and that's where attention and funding should be targeted.

While members of Congress have introduced bills to strengthen and expand the D.C. program — and as plans are underway to mark its 20th anniversary in January — even some proponents are saying the D.C. model is outdated and needs a refresh.

"It's great that it helps kids, but it's more of a policy dinosaur at this point in time," Enlow said.

A three-legged stool

Not only is the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program unique in that it provides federally funded private school tuition assistance only for qualifying students in the District of Columbia, it also was designed to give equal funding to the city's traditional public schools, public charter schools and the voucher program.

In FY 2023, the Scholarships for Opportunity and Results Act, or SOAR Act, sent $17.5 million each to the voucher program, District of Columbia Public Schools and the city's public charter schools for a total of $52.5 million.

D.C. voucher program and public schools share federal allocation

There were 1,707 voucher participants and 3,339 applicants last school year. In 2022-23, DCPS had 50,131 students and the public charter schools enrolled 46,392.

Voucher opponents say it's this three-pronged approach that helps keep the program alive, because it seems — at least on the surface — that public schools benefit financially.

"Many of the local leaders who were willing to support this voucher did so with the understanding that the other public schools in D.C. would get funding," said Garrett. "And [in] years of us saying we should defund the voucher program because it's unsuccessful and give more money to the D.C. public schools, we have been pushed back."

"The pushback has been [that] it's a three-legged stool … if you change it at all, the stool topples over," Garrett said. In other words, some local leaders have been hesitant to fully oppose the program, since it's channeling money into public schools.

Voucher supporters, meanwhile, also have frustrations. They say the program's design contributes to unnecessary and counterproductive rules for participating private schools and limits the number of students who can receive scholarships.

To start with, supporters say the scholarship tuition cap — $10,713 for elementary and middle school grades and $16,070 for high school for the 2023-24 school year — is too low. The average annual private school tuition in D.C. is $27,434, according to Private School Review, a company that provides data on private schools.

Additionally, choice advocates say the voucher program places too many restrictions on who can participate. First-time applicants must meet family income thresholds that are 185% of the federal poverty level, or $45,991 for a family of three. Returning students' family incomes cannot exceed 300% of the poverty level, which is $74,580 for a family of three this calendar year.

About 94% of D.C. scholarship recipients are Black or Hispanic, and the average annual income of participating families was $20,572 in the 2022-23 school year, according to Serving Our Children, the nonprofit organization that administers the program. That compares to an average household income in Washington, D.C. in 2023 of $156,367, according to DC Health Matters, an online portal of public health indicators.

The income caps — along with Congress' unpredictable annual appropriations process — make it difficult to plan for and guarantee future scholarships for current participants, program supporters say.

Participation of D.C. voucher students fluctuates year-to-year

Additionally, participating schools must meet several requirements, including being accredited, ensuring that core subject matter teachers have a bachelor's degree or greater, and undergoing annual site visits by Serving Our Children.

The schools also must agree to cooperate with a congressionally mandated independent evaluation conducted by the Institute of Education Sciences, a research arm of the U.S. Department of Education.

It's these types of rules that have led some schools to withdraw from the program over the years, said Lindsey Burke, director of the Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, an organization that advocates for free enterprise and limited government and has been a longtime supporter of the D.C. program.

Burke, who studied the issue for her Ph.D dissertation in 2018, found private schools in D.C. were split, with 48 participating and 49 not. Since the voucher program launched in 2004, 20 participating private schools had closed by 2018, and another seven converted into public charter schools, she said.

Some 22 private schools never participated and didn't want to, according to Burke's research. Interviews with these schools' leaders revealed they didn't join in because of requirements in the law, fear of future regulation, and the unpredictable funding method, Burke said.

To voucher opponents, the program lacks transparency. For example, they want to know how many scholarship students are enrolled at each school. They also express concerns about private schools discriminating against students based on gender, religious choices or disability status.

The private schools choose the students, and they don't have to take anybody they don't want to take.

Mary Levy

A Washington, D.C., resident opposed to private school vouchers

The D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program is "basically being promoted under false premises," said Mary Levy, a D.C. resident and former consultant with the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs.

The scholarship program is "saying that this is parent choice. It's not parent choice. It's a school's choice. The private schools choose the students, and they don't have to take anybody they don't want to take," said Levy, who used to work with the now-defunct Parents United for D.C. Public Schools, a group that advocated for funding for D.C. public schools.

Levy wrote a chapter about the D.C. scholarship program in a book, "The School Voucher Illusion: Exposing the Pretense of Equity," published in April.

How did the program start?

The voucher movement in the nation's capital can be traced to the late 1990s with the work of Virginia Walden Ford, a mother who wanted options for her son other than a neighborhood school she considered unsafe.

"I felt like he needed something different, but nobody could see it but me, and I found that that's what a lot of other parents felt," said Walden Ford. "Schools in D.C. were struggling and troubling, and we were watching our children get lost in the process that just didn't benefit them."

Walden Ford would go on to lead the push by parents to create the voucher program by collecting signatures, attending school board meetings and testifying before Congress. The story of her advocacy even became a movie released in 2019.

Everybody else seems to have those kinds of options — people with money, people that live in different parts of town, but our kids didn't.

Virginia Walden Ford

An activist who helped create the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program

Before her fight for vouchers, Walden Ford, by her own account, never imagined she would lead a movement — though she had been part of one as a Black child in the South.

She grew up attending segregated schools through 9th grade in Little Rock, Arkansas. But right before Walden Ford and her twin sister began 10th grade in 1966, her parents told them they would transfer to Little Rock Central High School, a nearly all-White school that had been slow to desegregate. Walden Ford did not want to go, knowing about the protests and harassment endured by the "Little Rock Nine," the first Black students to integrate the high school in 1957.

But her father — who served as the school district's assistant superintendent — wanted his daughters to set an example for their two younger siblings. When Walden Ford first enrolled in Little Rock Central High School, she noticed that the books and materials like science equipment were newer and more abundant than those in her former all-Black schools. However, she also encountered the racism she had feared.

One year, a White teacher refused to call on her and other Black students in class, causing her to fail geometry because participation made up 50% of the grade, Walden Ford recalls nearly six decades later.

"I think part of the reason I fight so hard now is because my experiences in high school were traumatic to me," said Walden Ford, who moved back to Little Rock in 2011 and continues to advocate for school choice nationally. "I want every child to have access to quality education. I want every child to finish high school with joy."

As a D.C. mom fighting for school choice many years ago, she said, creating the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program seemed like a logical step to boost the academic experiences for low-income children then attending poor-performing schools.

"The power of what happened was that people started understanding that kids could learn in different kinds of environments, and why not make those available to them?" Walden Ford said. "Everybody else seems to have those kinds of options — people with money, people that live in different parts of town, but our kids didn't."

Yet nearly 20 years after the first D.C. scholarships were awarded, Walden Ford is frustrated over the divisiveness surrounding the D.C. program — and private school choice programs elsewhere.

"I believe it has become about power, money, who does it first, and I believe it changed so much … that it stopped being about children and it started being about besting each other."

Tomorrow: What participants and research say about the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program — and what its future holds.