This is the fourth installment of a five-part series on ransomware in schools.

If a proposed Biden administration rule is finalized as drafted, school districts with 1,000 or more students — along with all state education agencies — would be required to report to the federal Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency within 72 hours of a disruptive cyber incident or within 24 hours of paying a ransom to cybercriminals.

But whether that threshold number of students will change upon issuance of final regulations, when those final rules will come out, and just when implementation would begin — all of those points remain unknown as of now.

CISA is still finalizing the rule implementing the reporting requirements for the Cyber Incident Reporting for Critical Infrastructure Act of 2022, or CIRCIA. And the agency has noted that it’s likely reporting won’t begin until 2026 due to regulatory delays.

Under the proposed rule issued in March, the requirement would apply to K-12 as well as a broad range of critical infrastructure sectors including healthcare, information technology and transportation. Although the proposed rule didn't cover K-12 private schools, CISA asked for input on whether to include them in the final rule.

And while CISA — the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s cyber defense arm — irons out the rule’s details, K-12 and cybersecurity leaders have questions about how the reporting requirement will be enforced and what will be done with all of the information collected from schools.

What should CISA do with schools’ reported data?

A big challenge that K-12 education, among other sectors, faces is that no national standard currently exists for reporting cyberattacks, making it difficult to truly gauge the problem.

In developing the proposed rule on reporting cyber incidents, CISA said a key principle is to enable the agency "to conduct threat analysis, track campaigns, and provide early warnings as required by CIRCIA.”

The federal reporting requirements will ultimately help boost resources for K-12 cybersecurity, especially as schools are often strapped to fund improvements on their own, according to Amy McLaughlin, project director of Cybersecurity and Network and Systems Design Initiatives at the Consortium for School Networking, or CoSN.

“I’m hopeful that this kind of rule, where we get specific data that’s consistently reported" will help with expectations around how cybersecurity for schools and districts is funded and supported, McLaughlin said.

But it’s still unknown how CISA will handle the data or share it. And some in K-12 wonder if CISA will publicly name districts and their specific cyber incidents.

If there are school districts out there just quietly paying ransom … [the] federal government doesn’t really have a handle on what the scope and scale of the problem is.

Lisa Plaggemier

Executive director of the National Cybersecurity Alliance

It’s unlikely that CISA’s aim is to “name and shame” districts that report cyber incidents or pay ransoms, said Lisa Plaggemier, executive director of the National Cybersecurity Alliance, a nonprofit that focuses on cybersecurity awareness and education.

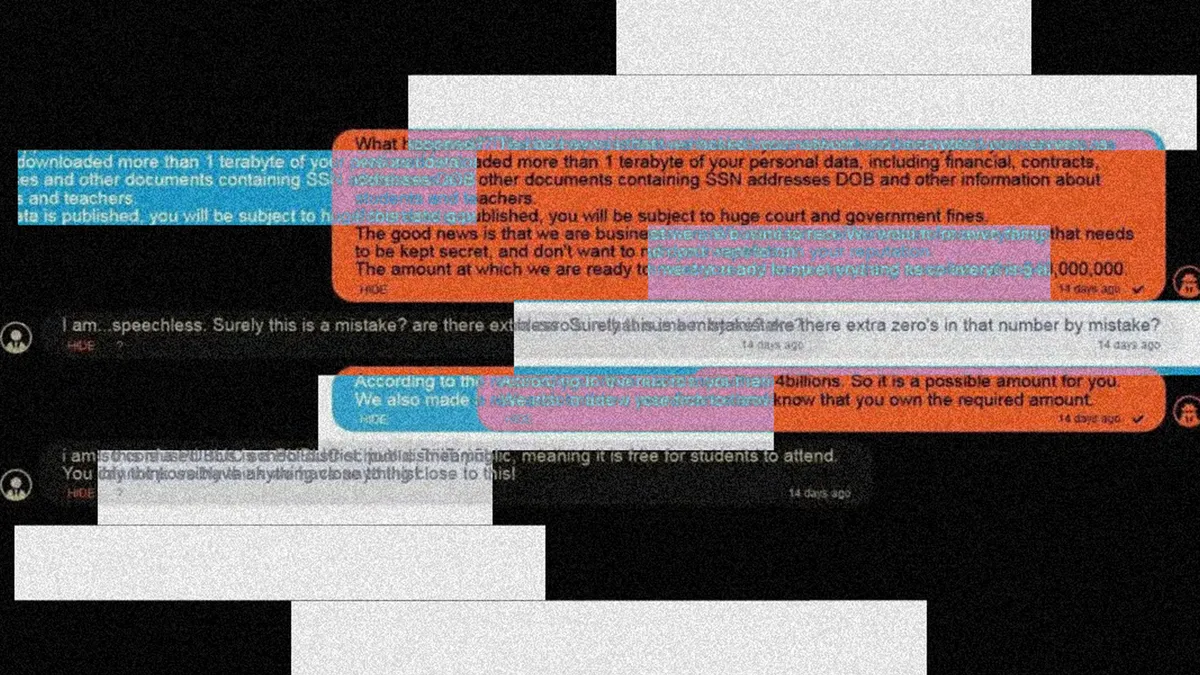

“I think CISA’s goal is to have more transparency, to have better data on how big the scope of the problem is,” Plaggemier said. “Because if there are school districts out there just quietly paying ransom … [the] federal government doesn’t really have a handle on what the scope and scale of the problem is.”

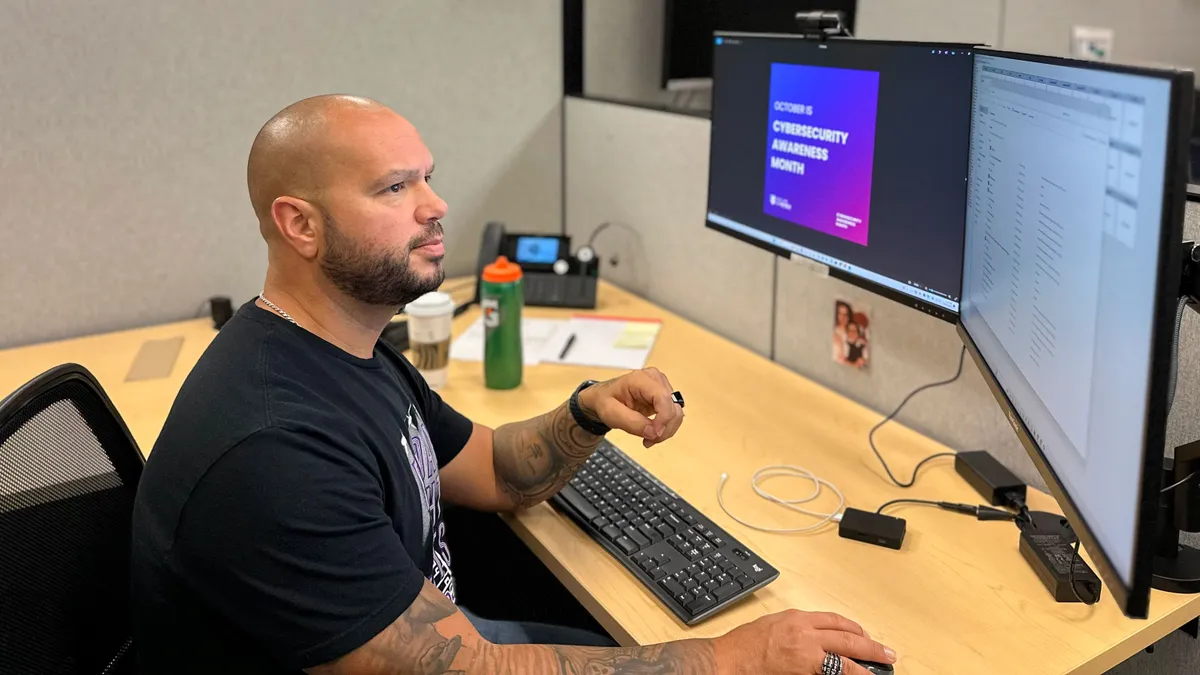

CISA should publicly disclose aggregated data on K-12 cyberattacks, said Will Brackett, director of IT services at Illinois’ Oak Park School District 97. “We should know, as a country, how hard is our K-12 and our higher ed being attacked?”

Yet whether districts are publicly named is ultimately up to CISA, said Brackett, who is also the cybersecurity advisory co-chair for CoSN.

As a taxpayer and a father of a former student, Brackett said he would want to know if his local school district paid a ransom to cybercriminals — “because that’s resources that my student now cannot use.”

But as a school district cybersecurity and IT professional, the thought of publicly disclosing such information “scares the crap out of me,” he said.

Even so, Brackett said publicly reporting a cyberattack is the ethical thing to do.

“One of the reasons I’m in K-12, it’s not just for a paycheck, it’s because I enjoy serving K-12, and there’s a huge responsibility for that,” he said. Brackett added that his sense of responsibility to parents, teachers and his community outweighs any concern he has over professional fallout he could face from disclosing a ransomware attack.

Brackett added that liability concerns are the main reason school districts are hesitant to disclose cyberattacks. While that’s an acceptable argument, he said, informing the public of such incidents is the more responsible decision from a policy standpoint. Plus, it would ultimately help to solve the widespread problem, he said.

Another reason schools may avoid announcing a cyberattack is the fear of victim shaming — both from within the school community and from the media, Plaggemier said. When that happens, the National Cybersecurity Alliance tries to combat that victim shaming narrative as much as it can, she said.

While schools targeted by cybercriminals might have implemented better cybersecurity practices, Plaggemier said, it’s important to first remember that they were victims of an attack.

“And it’s probably asymmetrical, because you have a school district trying to defend themselves against really highly skilled organized crime and/or a nation-state attack,” she said. “So that’s really not a level playing field.”

How does CISA define cyber incidents?

While CISA’s proposed rule would require schools to report a disruptive cyber incident within 72 hours, McLaughlin said it’s hard to know sometimes — depending on the kind of incident — if one has even occurred. It can be difficult, in the moment, to start the clock and gauge how much time has passed since an incident happened, because some cases are less obvious than others, she said.

Identifying a cyber incident is an “art form” in a way, McLaughlin added.

“It’s not like there’s a strict playbook,” she said. “Every single cyber incident that I've ever seen plays out slightly differently based on the adversary, the pattern of attack, what you learn and when you learn it.”

Brackett said he would like to see CISA more closely define what is a cyber incident. For instance, does accidental data loss that no one accessed from outside the district count as a cyber incident worth reporting?

We should know, as a country, how hard is our K-12 and our higher ed being attacked?

Will Brackett

Director of IT services at Oak Park School District 97

District networks also face a lot of “noise,” which could potentially be considered a cyber incident, Brackett said. Several bots could ping a district’s system within an hour, “but that’s just garbage on the network,” he said.

How can schools prepare for reporting cyber incidents?

With the implementation of the CIRCIA rules over a year away, cybersecurity experts agree that district IT leaders can use this moment to discuss resources and best practices with their superintendents and school boards.

Most important, school boards and district leaders should be aware that this reporting requirement is coming, and they should be ready for it, Plaggemier said. The pending implementation also gives IT leaders a good excuse to assess their districts' cybersecurity programs.

The National Cybersecurity Alliance offers training to sector leaders how to manage cybersecurity as a function of the organization. The program, called CyberSecure My Business, is expanding to teach school leaders in layman's terms how to better manage cyber risks, Plaggemier said.

Another crucial way schools should prepare for the reporting requirement is to make sure they have an incident response plan, McLaughlin said. That plan should set up a team that clearly articulates the roles, responsibilities and steps to be taken upon a suspected cyberattack.

Those steps should include when to contact a cybersecurity insurance company and when to assemble a response team, she said.

The response plan's timeline and procedures should also be updated to reflect the reporting process for CISA, a district’s cyber insurance policy, and any local or state requirements, McLaughlin said. Once that’s created, she said, district leadership teams need to practice scenarios for when to implement the plan.

Additionally, Plaggemier suggests that districts know the name and cell phone number for their local FBI field office agent in case of a cyber incident. That information should not be stored on a computer, she said, because IT leaders may not be able to access it during a cyberattack.

Plaggemier added that districts should reach out now for conversations with their local FBI officials, so they get familiar with one another — before a cyber incident unfolds.

News Graphics Developer Julia Himmel contributed data and graphics support to this story.