This is the first installment of a five-part series on ransomware in schools.

The Tucson Unified School District and Nantucket Public Schools seem to have little in common. Tucson schools, with 42,000 students, is one of the largest districts in Arizona and sits in a bustling urban area. Nantucket schools, on the other hand, enrolls fewer than 2,000 students and populates a small island off the coast of Massachusetts.

But in early 2023 — just one day apart on Jan. 30 and 31 — both school systems fell victim to ransomware attacks that disrupted operations, leading to school closures in Nantucket and the compromise of personally identifiable data in Tucson.

Ransomware — where threat actors use malware to block access to network systems and then demand payment to unlock it — has been ballooning in the K-12 sector over the last seven years, according to the K12 Security Information eXchange. Known as K12 SIX, the national nonprofit helps protect schools from cybersecurity threats.

An estimated 325 ransomware attacks hit public K-12 schools between April 2016 and November 2022. From that date through Oct. 3 of this year, schools have experienced another some 85 ransomware attacks, according to K12 SIX.

Adding to the pain, a handful of school districts were hit with ransomware twice between April 2016 and November 2022, according to K12 SIX data.

The numbers, it's important to note, can shift upon further investigation to determine whether the events were definitely ransomware attacks.

But Roberto Rodriguez, assistant secretary for the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, said an estimated five cybersecurity incidents hit K-12 each week.

393%

The increase in the number of ransomware attacks on K-12, from 14 in 2016 to 69 in 2022, according to data from K12 SIX.

Not only do these cyberattacks inflict logistical, legal and financial damage, they also take an emotional and physical toll on school communities, say education administrators and technology professionals.

Plus, there are national security concerns, given that perpetrators are often international criminals.

"At the end of the day, we're a country that offers a free and public education, and when an outside entity and a nation-state actor attacks that, they're not attacking just the school, they're attacking the concept of a free and public education and our approach to how we do things in the U.S.," said Amy McLaughlin, project director of Cybersecurity and Network and Systems Design Initiatives at Consortium for School Networking, or CoSN, a professional association for K-12 ed tech leaders.

Why is this happening?

One of the most significant factors putting a target on K-12's back is that the sector has rich digital assets but underresourced cybersecurity infrastructures. The assets are all in the information — names, birth dates, Social Security numbers, student disability status, financial details — that districts, private schools and the third party companies they work with are supposed to protect.

Yet many districts and public and private schools lack the technology or staffing to stay ahead of criminals and safeguard the sensitive data entrusted to them. The K-12 education sector, like some other industries, also has no federal mandatory and uniform cybersecurity standards for identifying and reporting attacks.

At the same time, bad actors are always finding new ways to take advantage of vulnerabilities.

At the end of the day, we're a country that offers a free and public education, and when an outside entity and a nation-state actor attacks that, they're not attacking just the school, they're attacking the concept of a free and public education and our approach to how we do things in the U.S.

Amy McLaughlin

Project director of Cybersecurity and Network and Systems Design Initiatives at CoSN

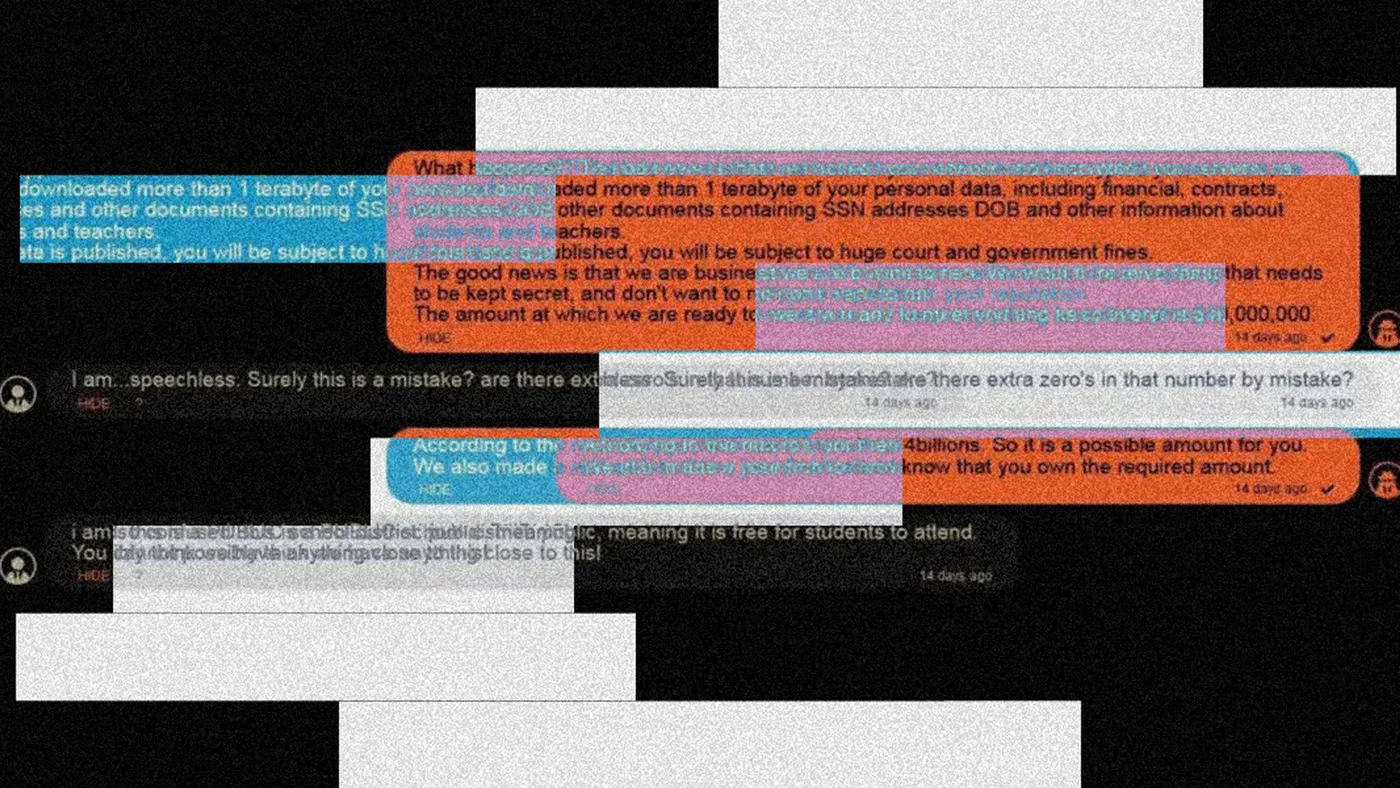

A concerning development, for example, is dual and triple extortion ransomware attacks. That is when threat groups steal and encrypt data, forcing victims to figure out both how to access their data and how to stop it from being released on the dark web or elsewhere. Student, staff and family data released in this way poses downstream risks for identity theft, credit and tax fraud, and other nefarious activity.

It's as if someone moved into your house, locked you out, stole your possessions — and then demanded payment to turn over the keys, said Richard Bowman, chief technology officer of New Mexico's Albuquerque Public Schools, which experienced a ransomware attack in January 2022.

McLaughlin adds, "They're out here stealing your data and charging you for it." Nation-state adversaries and criminal or terrorist organizations attack education entities "to fund their business model," she said.

Indeed, Doug Levin, co-founder and national director of K12 SIX, said the attacks are "100% about money."

A number of characteristics — including a lack of robust cybersecurity measures — make K-12 into attractive prey, Levin said. "We've been slow to implement common sense protections, like multifactor authentication, which makes us easier targets compared to other sectors," he said.

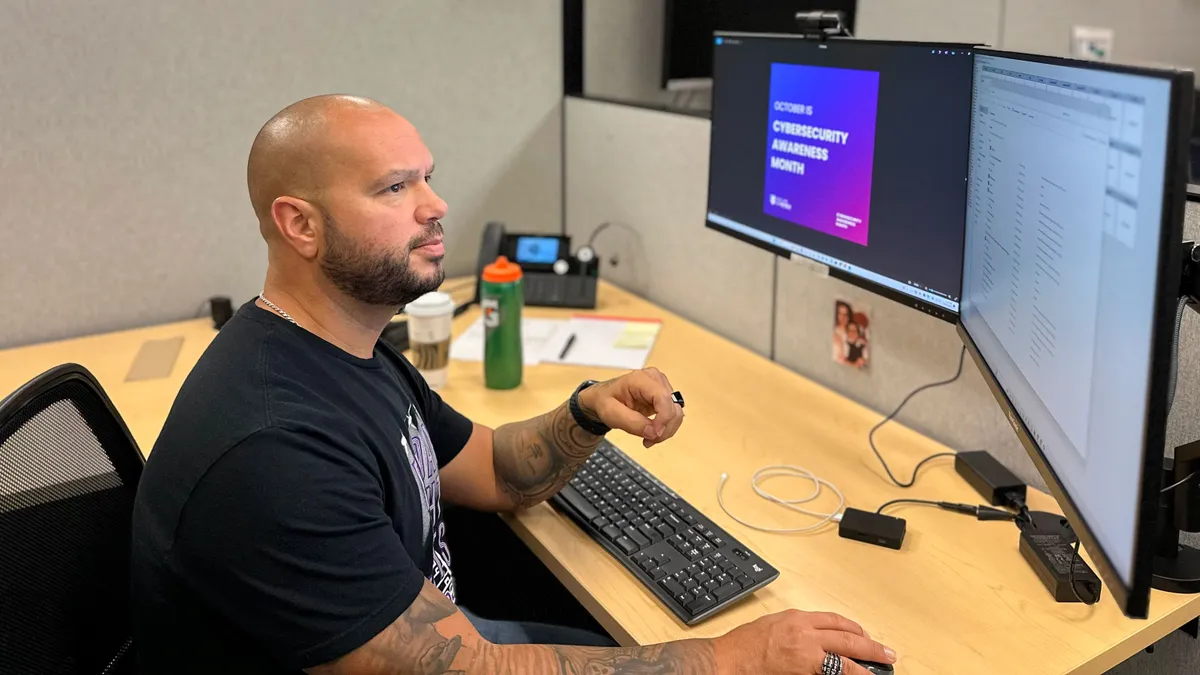

Other contributors include disjointed response protocols and underresourced cybersecurity staff. Two-thirds of districts had no full-time cybersecurity position in 2023, according to CoSN survey data. And 12% of districts said they don't dedicate any funds for cybersecurity.

A 2024 U.S. Department of Homeland Security threat assessment report said K‑12 districts have been "a near constant ransomware target." The federal agency blamed this on budget constraints of school systems' IT departments, a lack of dedicated resources, and cybercriminals' success in getting schools to pay ransoms.

In addition, districts are simply managing a lot of ed tech these days. During the 2023-24 school year, they used 2,739 different ed tech tools on average, an 8% increase from the previous school year, according to a report released earlier this year by Instructure and the company's LearnPlatform, which helps districts research and choose digital learning products.

People within schools and districts — educators, students, staff — are also for the most part trusting, caring and optimistic, educators and technology experts note. Educators often don't assume others are acting with ill intent. This attitude is needed to create nurturing school environments, but it also can give an advantage to criminals who prey on vulnerable systems.

What damage has this caused?

More than half – 62% – of "lower education" systems worldwide that are victimized by ransomware pay the criminals to recover their hijacked data, according to a 2024 report from U.K.-based cybersecurity firm Sophos. The data was based on a survey of 300 lower education IT and cybersecurity leaders in 14 countries.

The ransom payments averaged $7.5 million, according to the 99 lower education survey participants who had paid demands.

The average price for restoring data with backup technology — excluding ransom payments — was $3.76 million, or about the expense of 54 U.S. teaching positions. That average cost is more than double the $1.59 million figure from the company's 2023 survey.

According to Comparitech, a cybersecurity and online privacy product review website, the K-12 and higher education sectors lost 12.6 school days on average in 2023 from ransomware attacks. That downtime calculates to $548,185 per day, or about 123,744 school lunches for one day.

The companies and organizations that collect and report data about K-12 cyberattacks do so with a caveat — they say the data may be underreported. That's because there is no national mandatory reporting system.

The new federal Cyber Incident Reporting for Critical Infrastructure Act is expected to change that, however, when it takes effect sometime in 2026. CIRCIA will require state education agencies and school districts with more than 1,000 students to report to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency within 72 hours of a disruptive cyber incident and within 24 hours of making a ransom payment to cybercriminals, according to the proposed rule for implementing the provision.

In addition to financial fallout, ransomware can wreak havoc on productivity, teaching and learning — not to mention the emotional well-being of a school community.

"I think that the challenge — the hardest part and the biggest piece of this — is that the disruption can be really significant," said McLaughlin. For instance, if a district has to close schools due to a cyberattack, parents have to find child care, sports games have to be postponed, and state testing has to be rescheduled.

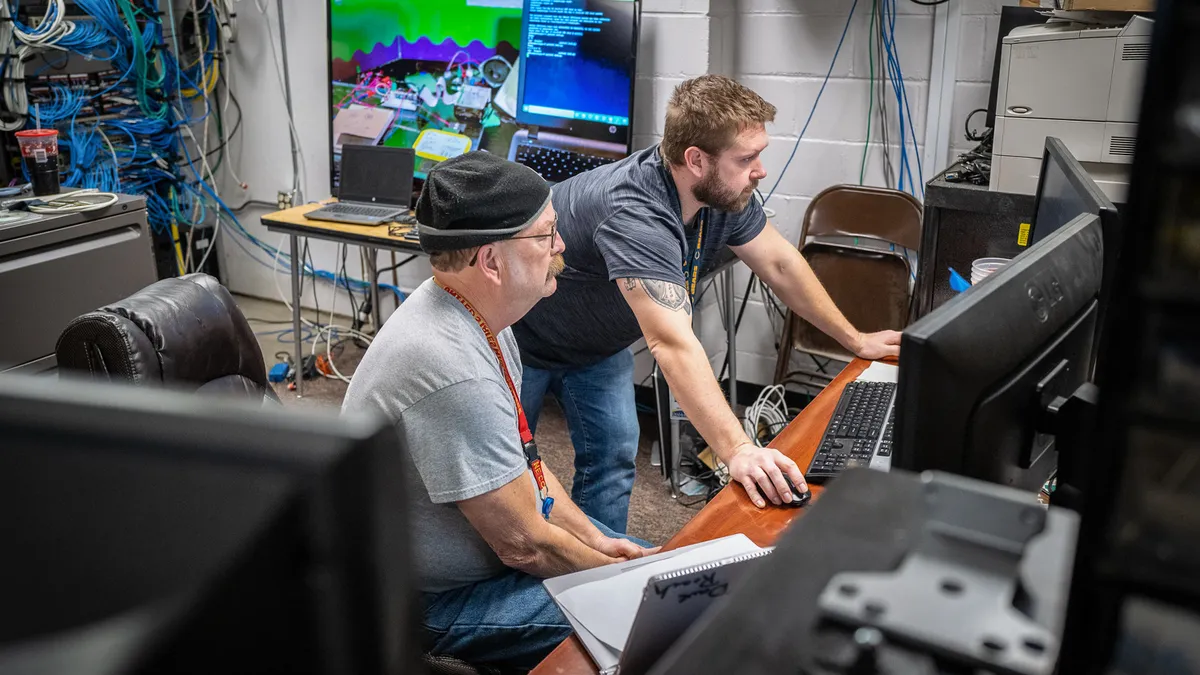

How are schools responding?

Once a breach is discovered and a ransom demanded, district or school response can vary with the circumstances. But experts recommend these steps:

- Work to limit the damage and preserve sensitive data.

- Decide if external help is needed from local and state authorities, cyber incident support teams or private vendors.

- Alert law enforcement, including the FBI and other reporting agencies like the Department of Homeland Security's U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team.

The FBI and CISA, as well as the nonprofit Multi-State Information Sharing Analysis Center, all discourage victims from paying ransoms as there’s no guarantee the files will actually be recovered. But some education economists and tech experts say making that decision is not so easy — as paying the ransom may be less disruptive or less expensive than rebuilding a school's network.

In some cases, districts have kept details of ransomware attacks hidden from the public and even staff. An investigative report by the Florida Sun Sentinel found that the 248,000-student Broward County Public Schools system waited five months to report key information to people impacted by a March 2021 cyberattack. In a Nov. 29, 2021, statement, the district said it was offering free credit monitoring to those affected and who requested the service.

Across the country, some school districts have had to respond to parents' demands for answers when personally identifiable information was compromised.

For instance, parents in a class action lawsuit filed Oct. 31, 2023, allege that "negligent and/or reckless failure" by Nevada's Clark County School District resulted in a ransomware attack that led to the release of sensitive data about teachers, students, families and former students.

"Despite knowing about this breach for almost a month, CCSD continues to fail to adequately inform those affected, continues to characterize what we understand was and may still be an ongoing breach of its systems as a single 'incident,' and continues to portray itself as an innocent victim rather than an accountable governmental body," said an undated statement from plaintiff law firm Sklar Williams. The case, Doe v. Clark County School District, remains open.

Liability is one reason school districts may want to stay silent about an attack. But there's another reason, too — shame.

"The topic of ransomware is rarely shared among organizations and is viewed as a scarlet letter or badge of dishonor to technology and security teams," said Lacey Gosch, assistant superintendent of technology at Judson Independent School District in Live Oak, Texas. Gosch's comment came during testimony on Sept. 27, 2023, before a U.S. House joint subcommittee hearing on combating ransomware attacks.

The 25,900-student Judson system fell victim to a ransomware attack on June 17, 2021, just a month after Gosch came to the district. A full investigation found the data breach affected about 429,000 people. The district paid a $547,000 ransom to ensure the threat actors deleted the stolen data, Gosch told the joint subcommittee.

District contractors had to install new cybersecurity software on each of the school system's 4,500 devices. In the end, it took Judson ISD more than a year to fully recover from the breach.

"The mentality that any organization is too small or insignificant to be affected by a cybersecurity breach is living under a false sense of security," Gosch said. "The truth is that cybersecurity events in organizations need to be viewed not as improbable but as absolute. The question is not if it will happen but when it will happen."

How are districts protecting themselves?

After years of victimized school districts suffering from frustration and shame, there's been growing momentum at local, state and federal levels to fight back through improved prevention, recovery and response practices.

Preventive measures like multifactor verification for accessing files are some of the leading defenses, Levin said. "The best thing is to not be a victim, right? If you're a victim, I think you're faced with a series of bad choices at that point," he said.

To safeguard schools, districts are investing in cybersecurity insurance and taking advantage of free tools and resources from CISA. Earlier this month, the White House Office of the National Cyber Director launched an initiative to encourage districts to adopt free protective domain name system services that prevent connections to malicious website domains.

Education advocacy groups, like CoSN and the State Educational Technology Directors Association, are also assisting districts.

The best thing is to not be a victim, right? If you're a victim, I think you're faced with a series of bad choices at that point.

Doug Levin

Co-founder and national director of K12 SIX

States are likewise stepping up to help. The Georgia Department of Education, for example, dedicated nearly $1 million in 2022 to provide every district in the state with licensing for a cybersecurity platform, through a contract with the Georgia Technology Authority. The platform allows districts to pinpoint their vulnerabilities and provides recommendations for improvements.

And CISA, along with the federal Education Department, created a Government Coordinating Council earlier this year to address hardships districts face in preventing, responding and recovering from cyberattacks.

The council is made up of school administrative organizations representing principals, superintendents, school business officials, special education directors and others.

It serves as an information-gathering and collaborating body to better understand K-12 cybersecurity challenges. It is also documenting best practices and brainstorming potential solutions, such as a dedicated technical assistance center, said the Education Department’s Rodriguez.

Congress has not provided the Education Department with a dedicated funding stream for supporting cybersecurity measures in school districts and state education agencies, according to Rodriguez.

"We are hearing from districts around the country — urban, rural and suburban — about the challenges that they face," said Rodriguez, adding, "We think that preventative approach is really something that has great potential, and we should be doing more with districts across the country, especially those districts that don't have more sophisticated infrastructure."

Cybersecurity Dive Senior Reporter Matt Kapko contributed background reporting and News Graphics Developer Julia Himmel contributed data and graphics support to this story.