Early signs of a decline in teen opioid-related fatalities are giving researchers and advocates hope that school-based opioid awareness campaigns are starting to have an impact.

In the second half of 2023, teen opioid-related deaths decreased slightly — marking the first drop seen in recent years — but the fatality rate still remained more than twice as high as before the pandemic, according to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

The KFF analysis revealed 708 drug-related adolescent deaths in 2023, which were mainly due to opioids. That is down from 721 fatalities in 2022, but up dramatically from 253 in 2018, the analysis found. The data from 2023 is not considered final, KFF noted.

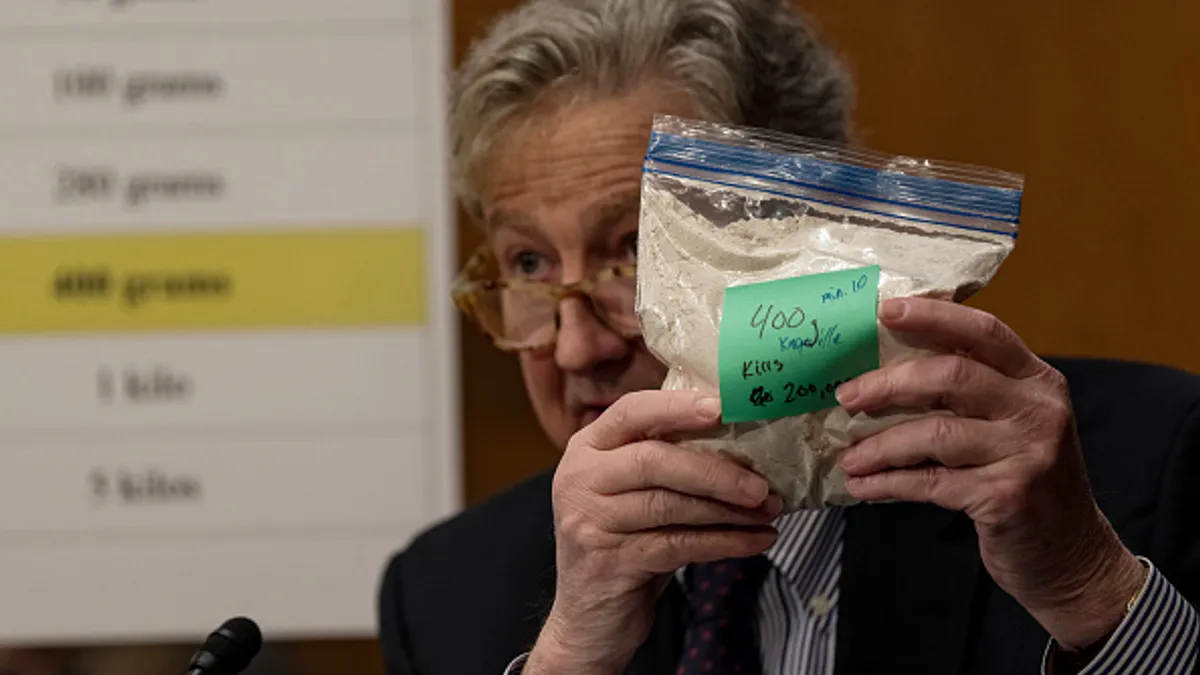

Fentanyl is driving drug deaths in adolescents

"While it is too early to determine what the direction of overdose deaths may be, factors that may have contributed to the small decline include a decrease in pandemic-related stressors along with policies aimed at reducing overdose deaths," the KFF analysis said.

Fatal opioid overdoses in youth saw sharp increases before and during the pandemic, with drug mortality rates climbing faster among teens than the general public, according to a study published in September in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

That's mainly due to fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, being illegally added to fake pills that resemble Adderall, Vicodin, Xanax and other prescription medicine, the research found.

Seven of 10 pills seized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration contain a lethal dose of fentanyl, the agency said. Even a tiny amount of fentanyl — 2 milligrams — can be lethal.

The National Crime Prevention Council, a nonprofit anti-crime advocacy group, and others warn that social media is partly to blame for facilitating the sale of these fake pills to teens.

Lessons in schools

In response to concerns about the increase in teen opioid-related deaths, local and state governments, along with federal agencies, have developed awareness campaigns and curricula.

Nine states — Oregon, California, Mississippi, Illinois, Texas, Washington, Alabama, Virginia and West Virginia — have mandated opioid prevention curricula in schools in recent years, according to Song for Charlie, a nonprofit that aims to raise awareness about the dangers of fentanyl.

The Oregon Department of Education in October released publicly accessible lesson plans about preventing and responding to fentanyl overdoses that focus on "strengths-based norms rather than shame or fear-based tactics." Beginning this school year, all Oregon school districts and public charter schools are to use the lessons in grades 6-8 and at least once in high school.

States and school systems have also expanded access to naloxone, a medicine that can be administered by spray or injection to quickly reverse an opioid overdose. Some state and local prevention education programs highlight Good Samaritan laws that protect people who provide help during an overdose situation from arrest or prosecution for certain crimes.

Surveys conducted by Song for Charlie show growing awareness among youth about fentanyl. An April 2024 survey found 67% of Oregon teens knew about fentanyl being used to make fake pills. Nationally, that compares to 27% and 36% of teens, respectively, in 2021 and 2022.

Having a school-based curriculum about the dangers of illicit opioids is critically important but unlikely to solve the youth fentanyl crisis on its own, said Jennifer Epstein, director of strategic programs for Song for Charlie. Epstein's son Cal died at age 18 in 2020 after unsuspectingly taking a fentanyl-laced pill.

Epstein said parents need to have regular conversations with their children about the dangers of illicit opioids and other substances.

"It's important for a family to reinforce the messages that are being taught in the school and for them to bring their family's values into the discussion," she said. "When a parent opens up those conversations in a non-judgmental way, it invites the young person to come back to them if they have questions or if they have concerns."

Epstein pointed to a Song for Charlie resource called The New Drug Talk that can help families with these difficult conversations.